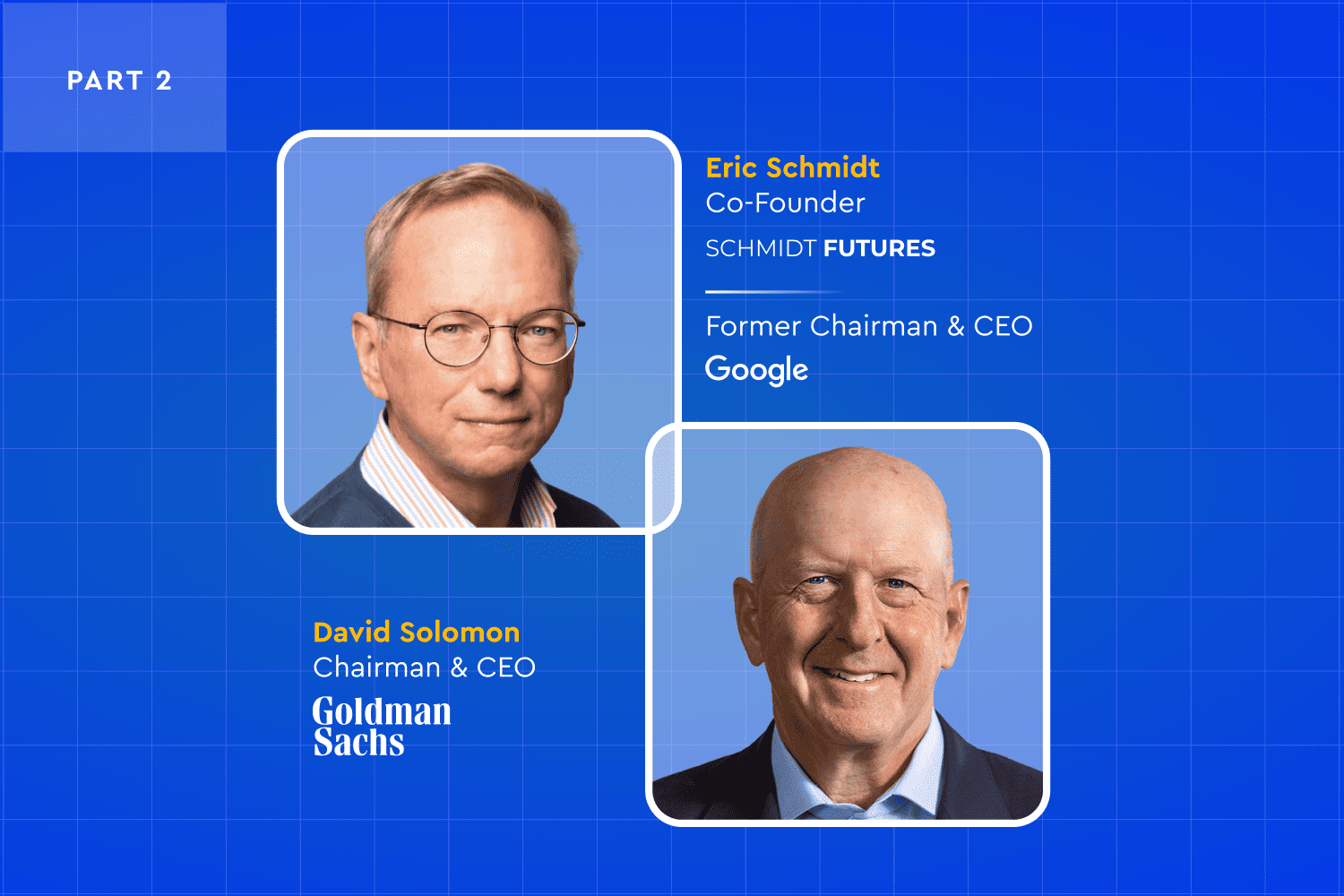

AlphaSense remains committed to its mission of revolutionizing the way professionals make crucial business decisions through the potential of AI. Looking ahead to an AI-driven future, we brought together two influential figures in the realms of technology and finance: Eric Schmidt, Co-Founder of Schmidt Futures and Former CEO & Chairman of Google, and David Solomon, Chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs. In this enlightening conversation, we delve into the unfolding landscape of generative AI (genAI), its swift expansion, and the consequential business dynamics of this rapidly evolving technology.

In the below discussion, Schmidt and Solomon explore what’s next for genAI and its profound implications for both commerce and society at large. They address crucial questions within the genAI domain, such as identifying industries ripe for disruption, elucidating the uncertainties and hazards linked to extensive reliance on this tech for information, and anticipating shifts in societal behaviors. You can read part one of the conversation about the rise of genAI, certain LLMs, and the potential economic consequences of new technology here .

This edited Q&A provides insight and clarity, but for the complete conversation, the full video conversation can be accessed at alpha-sense.com/genai.

—–—

Solomon: AI’s been around for a long time but can you discuss the trajectory and evolution of AI compared to other software platforms?

Schmidt: We’ve never seen anything this fast. Let’s look historically at milestones. In 2011, an AI group at Google figured it out. The program was watching YouTube and discovered the concept of a cat. It didn’t know it was looking for a cat. It discovered it. The first discovery of a concept by computers.

In 2015, we won the Go Game, which was thought to be unwinnable by computers. In 2017, a different group at Google built a thing called transformers, which is the T in GTP. Then a completely different company, OpenAI, figured out a way to build GPT1, 2, and 3.

They weren’t trying to do what they did. They were actually trying to solve problems in science, but they had all of this language. They turned it on language, and all of a sudden it did this incredible job at writing even if it was wrong. It was a brilliant writer with wrong facts.

It was through using a technique called RLHF where they ultimately built the thing called ChatGPT in November of last year. Remember, this is all less than a year old, and, boom.

When OpenAI released ChatGPT, they didn’t think anyone would notice because they were working on a much more powerful model, CPT4. They had forgotten that everyone could be surprised.

Solomon: With the rise of AI, do you think that the balance of power among these large tech companies is shifting?

Schmidt: There’s a limit to how quickly folks can change. At one point last year, 25% of the market value of the S&P was from six tech companies.

In the case of Apple, they have yet to exploit the power of generative AI. The obvious case is to replace Siri with something much more capable.

We don’t know how they’re going to do it yet. Remember, they’re not trying to solve the general intelligence problem, they’re trying to solve the problem of getting you to love their products more, which means they’re going to have different solutions in different parts of their businesses.

In Microsoft’s case, they’ve made a huge investment in OpenAI. They started by saying, “Let’s make programmers more productive.” There’s evidence, if you use Microsoft tools, the computer writes roughly half the code.

If you think of it as me plus the computer is equal to two me’s that’s a big deal. Doubling the productivity of programmers, which I think is the first thing that Microsoft has done, is a real win.

I’ll give you a simple recent example. I had to write a memo about AI to the President. I don’t write very well, so I wrote the memo with lots of details and sent it to GPT4, and I said, “Rewrite this. Don’t change the math.”

GPT4 wrote it, much better than I could, and I sent it to the President. What’s the value of that to me? A lot. To you, to any of us.

Solomon: Absolutely.

Schmidt: These are, and will be, embedded in our workflows. They’ll be in Word and Excel. They’ll be in Gmail. They’re already in GDrive and so forth. The next step is where they go from simply helping me with a task to generating what I should be doing.

For you as CEO, you have these incredibly highly paid, highly talented, highly educated people. You want to increase their productivity. You don’t want them typing, you want them thinking. The ideal scenario is the computer is working with them, understands them well, and is highly targeted to what they do. It says, “Consider this.”

Imagine a situation where, when you’re doing search or doing research, not only does it suggest what you asked but it asks the question—offers the questions you should have asked and the answer.

What I want is to say to the computer, “Here’s my idea,” and the computer says, “Here are the facts that support your position, Here are some alternative theses that you should consider, and here’s why they might be relevant.” That would make me so much smarter.

Solomon: So you’re talking about this being completely integrated into everybody’s operating systems.

Schmidt: Exactly.

Solomon: Let’s step away from businesses right now and talk about everyday people and the way they live their lives. Does AI become an everyday part of how we operate on platforms as individuals?

Schmidt: I think it depends on who you are. For kids, it’s both incredibly important and incredibly frightening because kids are learning how to form relationships. Imagine if your best friend as a kid is non-human.

There’s a lot we just don’t know. We don’t know what that does to them cognitively. We ended up running this massive experiment over 20 years—without any testing or restraints—using social media to see what happened, and it wasn’t such a good outcome. We want to avoid having a negative impact on young people.

We don’t know if people will get attached. We don’t know if people anthropomorphize these sorts of things. The problem you stated in business is much easier—I just want to generate more revenue. But the impact on society, where the definition of who we are as humans is changing, is a very big deal.

The industry believes, in five years or so, you’ll have solved all of these problems of recency bias, hallucinations, and so forth, and it’ll also be able to do step-wise planning. At some point, these systems will have some kind of agency on their own. They’ll be able to initiate things. Today, they can’t.

When they can initiate things and it’s doing its thing and you’re doing your thing, how do you trust it? How do you constrain it? How do you know what it’s doing? You say, “What are you working on?” and it says, “I’m working on physics.” But in fact, it’s working on biology because it’s learned how to lie. We don’t even have a language to discuss these things.

Solomon: What can we learn from our 20-year experiment in social media? What should we be doing with social media that can help us as we go prepare for what is an exponential change in the way these things affect society?

Schmidt: A critical view of social media, which is easy, is the incentives are not in alignment with humanity. Social media is organized around revenue. The way you get more revenue is you get more usage. The way you get more usage is more outrage. That rule, I suspect, applies to LLMs and AI in general.

We have to address the question of whether the goal of these companies is to maximize revenue or to maximize communications. They appear to be maximizing conflict. I have every reason to believe the union of large language models and social media makes them much, much worse because they can do more targeted misinformation. Also, you have the ability to generate fake images and drive people crazy.

It makes perfect sense that, if you’re an evil social media CEO, you want to produce misinformation that will cause people to start rioting because you make more revenue out of it. I’m not suggesting people are doing it, but it’s the alignment problem with their interests.

We have to acknowledge that we as human beings collectively have these defects. The answer among the allegedly smart people is we’ll just better educate people. We know that doesn’t work. We know about recency bias. We know about first principles. We know that if falsehoods are repeated over and over again, they become true.

Collectively, we need a better discussion about this. In the American political system—not to be a downer here—I think 2024 is likely to be a complete disaster because of misinformation. Both parties are aware of it, but neither party is willing to take the steps to regulate it because they’re afraid of being disadvantaged against the other side.

We have to get to a point where leadership in our country fundamentally believes we’re better off regulating the worst aspects of these things, and we’re not there yet.

Solomon: When you think about the impact on society and business broadly, are there industries that won’t be disrupted by this?

Schmidt: In general, the disruption occurs first in the industries that have the most amount of money and the least amount of regulation. So the tech industry and programmers is an obvious one. Places like Hollywood are another example. They move quickly. They have a lot of money. Things change quickly.

Here at Goldman Sachs, and your peer competitors, you move quickly even though you have regulators. The industries that are both heavily regulated and slow-moving include education, healthcare, national security, and the military. Somebody has to fix that.

In the military, many of our valued enlisted people are sitting, watching all day. That makes no sense. Have the computer do the watching. They can be sitting in the breakroom and the computer says, “Oh, something bad happened.” It makes no sense to have humans watching something and getting bored.

The principle you’re going to see, which has always been true of automation, is that the most dangerous and most boring jobs will get replaced first. And then eventually, we move up the ladder.

The above conversation concludes the second part of our three-part blog series. Stay tuned next week for the third part of this riveting interview: Solving the World’s Greatest Problems with AI: Solutions and Hurdles. You can read part one on the future of genAI in business.

If you’d like to read the entire interview now, you can download the full report on the future of generative AI in business. If you’d rather listen to the entire interview while you work or on your morning commute, access the on-demand webinar here.