Personal consumption expenditures as a percentage of GDP have declined five out of the past six quarters. Even before the pandemic, the U.S. was veering away from the received wisdom that “consumers drive the economy.”

“Many who have been laid off are benefiting now from the one-time stimulus checks and temporary increase in unemployment insurance benefits enacted in the CARES Act,” Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell wrote in June. “The supplementary UI will end this summer. At that point, it will be difficult for many families to meet their financial commitments—rent, food, utilities, and other payments—if the economic downturn continues and the benefits are not renewed.”

Summer is almost over. What happens now if consumers—who might have just received notice that their temporary furlough has just been reclassified as permanent unemployment —can no longer pick up the slack? Where will the spending come from?

Takeaways

- Personal consumption as a percentage of GDP is declining, so consumers no longer drive the economy to the extent they used to.

- If there is to be a recovery from the coronavirus-induced recession, the consumer sectors might not be reliable engines, and the Information Technology sector might not be as strong a bet as it looked to be last week.

- Impacts on the Consumer Discretionary and Health Care sectors could be severe.

- The new drivers might be government spending, exports, agriculture, and mining, similar to what is occurring in Italy.

Sectors in decline

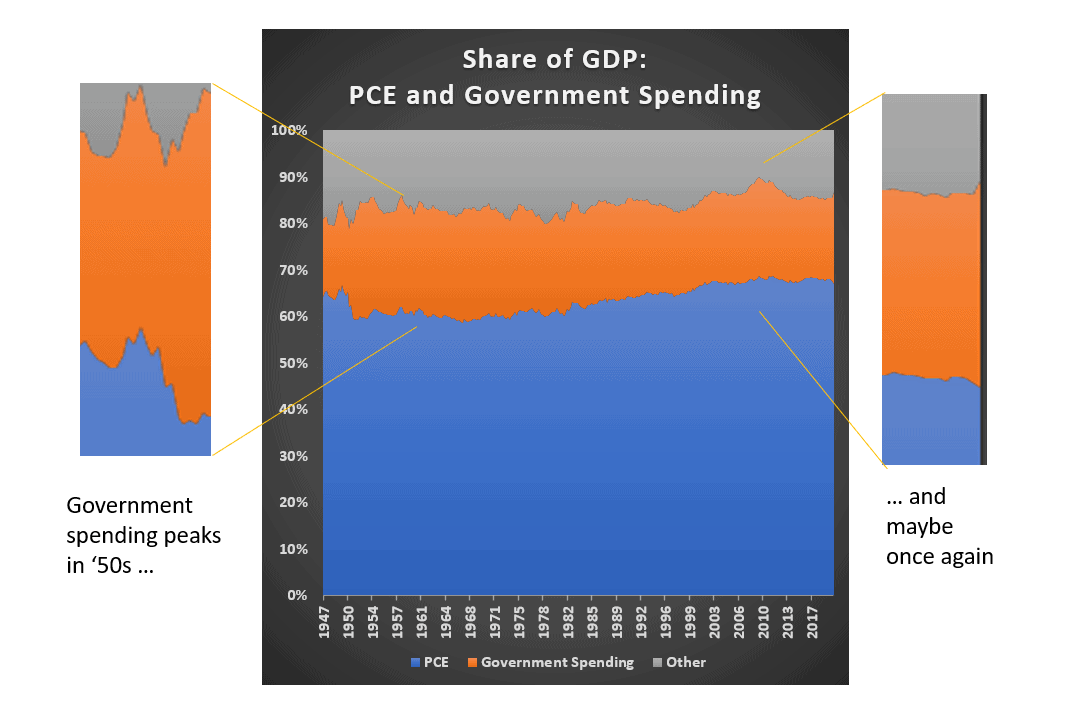

Since the end of World War Two, personal consumer expenditure (PCE) has accounted for no less than 58.6% of gross domestic product in any one quarter, Bureau of Economic Analysis data reveals, reaching a record high in the third quarter of 2011 of 68.7%.

“[T]he recent drop in core PCE inflation is mainly attributable to large declines in consumer demand for goods and services stemming from COVID-19, which have more than offset any upward inflation pressures due to supply constraints in some sectors,” according to a San Francisco Fed report.

Considering the Fed’s own weak-dollar stance tends to promote inflation, it’s a telltale sign of declining demand when the price pressure is off for such a key component of the economy. Some of that decrease relates to lower prices and demand for fuel, which has a lot to do with the pandemic, but also relates to the current bottoming of the oil cycle and the secular trend toward lower reliance on fossil fuel.

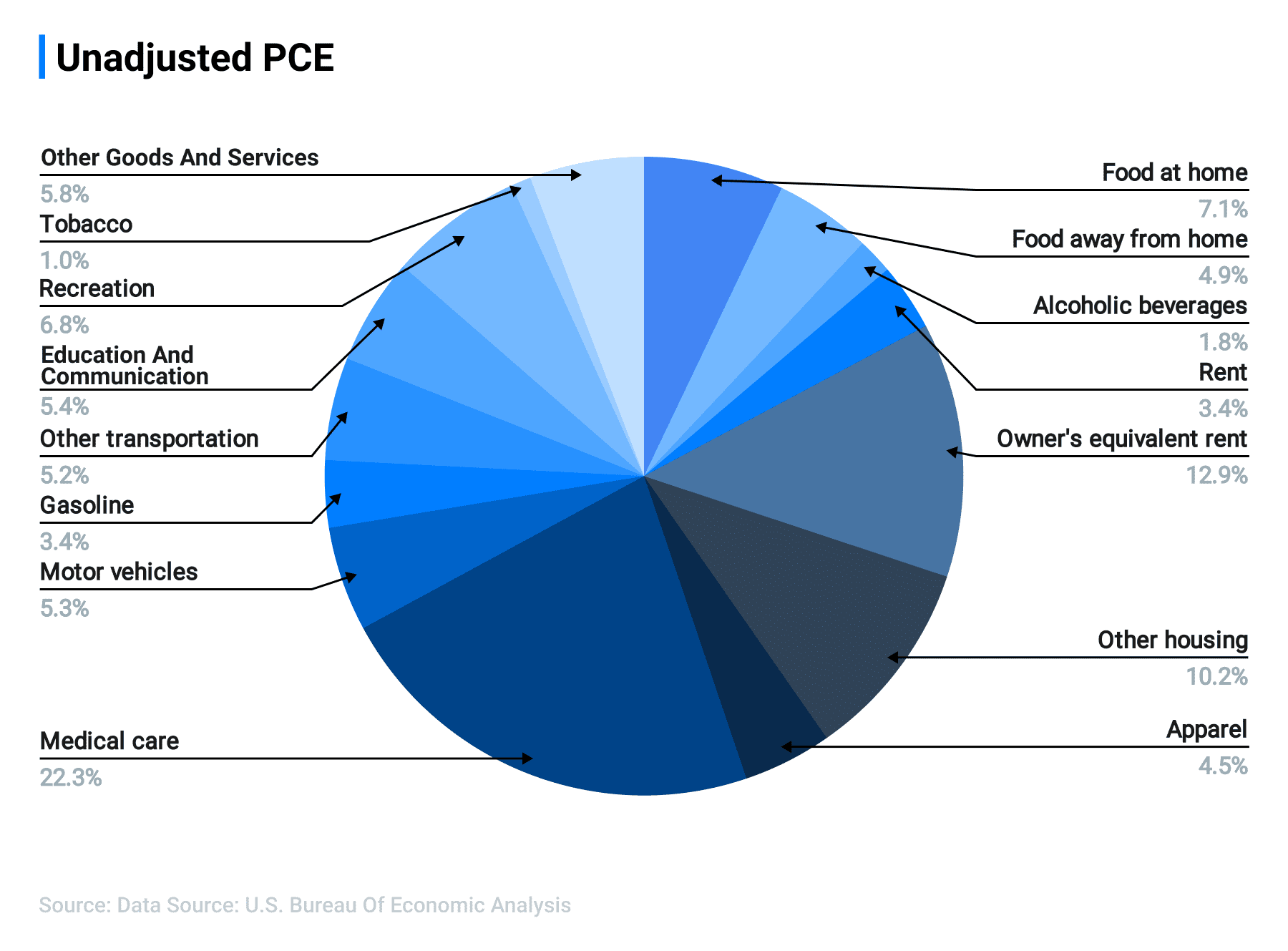

Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis |Almost two-thirds of PCE is spent on services, chiefly housing and health.

If you accept the premise that the consumer’s reign is over, then it follows that the sectors which generate the chunkier portions of PCE will decline until well into the next recovery. Chief among these is Consumer Discretionary, which includes cars, homes, and furniture; despite the recent spike in this sector, long-term prospects might not be all that great.

Consumer Staples could hold its own, but that’s just because commodity prices are going up while we still have to stock our kitchens and baths. The Health Care sector might have a split personality for a while. While delivering services through doctors’ offices and hospitals or treatments through pharmacies could sag, technology could still thrive in this environment, even without a worldwide pandemic to vaccinate against.

Let’s also rule out Energy as an engine of the next recovery due to its boom-bust nature; it traditionally hasn’t rallied until late in the business cycle, and the Information Technology sector might not be as strong a bet as it looked to be last week.

Wall Street socialism

It’s not news. John Maynard Keynes and his spiritual descendants have been telling us since at least 1936 that government spending leads to economic expansion. The only thing that’s new is the degree to which it can be deployed without impoverishing an otherwise healthy nation. The Economist just published an article titled “Governments can borrow more than was once believed”. It shows how advanced economies can perform well even if national debt exceeds 120% of GDP – you know, like Italy in 2014. Even before the pandemic, the U.S. had abandoned its squeamishness and borrowing all the money it could, and it wasn’t alone.

“Sceptics insisted that such borrowing would drive interest rates up,” the article states. “But as the years went by and interest rates remained stubbornly low, the notion of borrowing for fiscal stimulus started to seem more tenable, even attractive. Very low interest rates mean that economies can grow faster than debt repayments do.”

So government spending is likely to become the engine that drives the economy. We who work in Financial Services or are otherwise Wall Street-adjacent can all put on sackcloth and ashes as we mourn the passing of unfettered market capitalism but, as every single one of us has said at some point, “It is what it is.”

Data Source: Federal Reserve | During the 1950s – when PCE as a percentage of GDP was at its lowest point – government spending accounted for as much 25% of the U.S. economy.

It remains to be determined what sectors the government is likely to favor. A good guess would be those that favor exports, considering that the Fed is keeping the greenback so weak that even the Mexican peso is appreciating in dollar terms. It would also make sense because, since the end of the Great Recession, net exports have been a persistent 2.5% drag on GDP.

The biggest American exports are agricultural. We send a lot of meat and poultry abroad, but they come in second place to soybeans. Other leading exports include fuel, aircraft, cars, car parts and pharmaceuticals. One bright spot is the $57 billion-per-year industrial machines export business. If we provided the same kind of export supports as some other countries, we could run the table on these. We should also consider how America’s rich supply of natural resources can be leveraged. As ecologically objectionable as it might sound, metals and mining as well as pulp and paper are viable options.

Lastly, there’s still the services side of the economy, and we export a lot of that, particularly around intellectual property. While software might not be the way to bet considering the current retrenchment of Information Technology stocks, we still make good movies, TV shows, and video games.

In an ironic twist, our export market for financial services and insurance – about $76 billion per year – is half as large as it is for IP. Wouldn’t it be ironic if government spending should prove instrumental in saving the financial industry? Oh, that’s right. It already did. Nevermind. Irony is dead.